Bible Commentaries

Ellicott's Commentary for English Readers

1 Samuel 2

II.

(1 Samuel 2:1-10) The Song of Hannah.

EXCURSUS A: ON THE SONG OF HANNAH (1 Samuel 2).

The song of Hannah belongs to that group of inspired hymns of which examples have been preserved in most of the earlier books. Genesis, for instance, contains the prophetic song of the dying Jacob, Exodus the triumph hymn of Miriam, Numbers the glorious prophet song of Balaam, Deuteronomy the dying prayer and prophecy of Moses; Judges preserves for us the war song of Deborah.

The Book of the Psalms was a later collection of the favourite sacred hymns and songs of the people, written mostly in what may be termed the golden age of Israel, when David and Solomon had consolidated the monarchy.

Each of the greater songs embedded in the earlier books seems to have marked a new departure in the life of the chosen people.

This is especially noticeable in the prophetic song of Jacob, which heralded the period of the Egyptian slavery, and pointed to a glorious future lying beyond the days of bitter oppression. Miriam sung of the triumphs of the Lord; her impassioned words introduced the free desert life which succeeded the slavery days of Egypt. Moses’ grand words were the preparation for the settlement of the tribes in Canaan.

Hannah was impelled by the Spirit of the Lord to make a strange announcement respecting her boy Samuel. She had learned by Divine revelation that he was to be God’s chosen instrument in the future: first, as the restorer of the true life in Israel—which was then beginning to forget its God-Friend; and afterwards, as the founder of a new and kingly order of governors, who should unite the divided tribes, and weld into one great nation the scattered families of Israel.

It is probable that these “poems,” which we find embedded in the oldest Hebrew records, were preserved in the nation, some as popular songs, sung and said among the people in their public and private gatherings as the best and noblest expression of their ideal national life; some as even forming part of the primitive liturgical service of those sacred gatherings of the chosen people which subsequently developed into the synagogue, the well-known sacred assemblies of Israel.

The various compilers or redactors of the several Old Testament Books, according to this theory, gathered these poems, hymns, and songs from the lips of the people as they repeated and chanted them in their sacred festal gatherings.

EXCURSUS B: ALLEGED DIFFICULTIES IN THE ASCRIPTION OF SONG TO HANNAH (1 Samuel 2).

The advocates of a later date for the song of Hannah, with some force allege two points in the composition, which they say forbids their ascribing the “song” to the mother of Samuel, or even to the period in which she lived. It will be well briefly to examine these. First, the “song,” they say, is a triumph song, celebrating a victory over some foreign enemies. Such a theory, however, completely misinterprets the whole hymn. Nowhere is a victory spoken of, and the song contains only one allusion (1 Samuel 2:4 : “The bows of the mighty men”) which has anything to do with war; and this solitary passage contrasts the mighty bowmen with the stumbling or weak ones, and shows how, under the rule of God, the warrior is often confounded, and the weak unarmed one strengthened. It is, in fact, only one of several vivid pictures painting the marvellous vicissitudes which, under God’s providence, so often happen to mortals. The strong often are proved weak, and the weak strong. The foes alluded to in the hymn of Hannah are not the enemies of Israel, but the unrighteous of the chosen people contrasted with the pious and devoted.

Secondly, the “song” in 1 Samuel 2:10 assumes the existence of an earthly king in Israel, whereas when Hannah sung no king but Jehovah was acknowledged by any of the tribes. Erdmann, in Lange’s Commentary, well observes, in explanation of this, that “at the period when Hannah gave birth to Samuel it was incontestable that in the consciousness of the people, and the noblest part of them too, the idea of a monarchy had then become a power which quickened more and more the hope of a realisation of the old promises that there should be a royal dominion in Israel, till it took shape in an express demand which the people made of Samuel. The Divine promise that this people should be a kingdom is given as early as the patriarchal period (Genesis 17:6; Genesis 17:16. See too Genesis 49:10; Numbers 24:17; Numbers 24:19; Deuteronomy 17:14 to end of chapter). At the close of the period of the judges, when Hannah lived, the need of such a kingdom was felt the more strongly because the office which was entrusted with the duty of forming and guiding the theocratic life of the nation, namely, the high priestly office, was involved in the deepest degradation.”

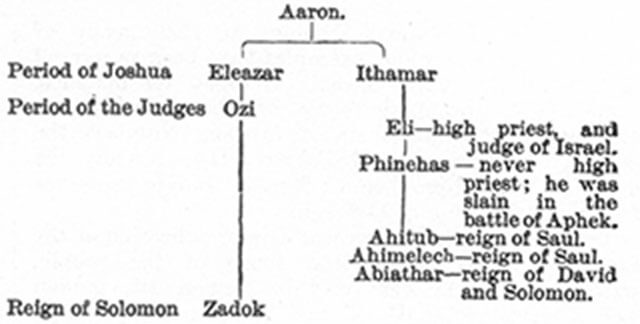

EXCURSUS C: THE HIGH PRIESTHOOD, AND THE FAMILY WHICH HELD IT (1 Samuel 2).

The supreme dignity in Israel was held by the family of Eleazar, the son of Aaron, until the death of the high priest Ozi. We are not in possession of the circumstances which led to the transference of the office to Eli, the descendant of Ithamar, the younger son of Aaron; probably the surviving son of the high priest Ozi, of the house of Eleazar, was an infant, or at all events very young, when his father died, and Eli—his kinsman, no doubt—had probably distinguished himself in some of the ceaseless wars in which the people during the stormy period of the judges were continually involved, and was in consequence chosen by the popular voice to the vacant dignity. After the death of Eli and his two sons, Hophni and Phinehas, the high priestly dignity never seems to have recovered its ancient power and dignity. The eyes of Israel were turned first to Samuel, and then to Saul and his royal successors, David and Solomon.

During the lifetime of Samuel, Saul, and David, though shorn of its old proportions and exposed to many vicissitudes, the high priesthood continued in the family of Eli, who was succeeded by his grandson, Ahitub, the son of Phinehas. In the days of Saul, Ahijah, or Ahimelech, the son of Ahitub, gave David the shewbread to eat at Nob, and was for this act murdered by King Saul, together with all the priests then doing duty at the national sanctuary. His son, Abiathar, escaped the massacre, and was allowed to assume his father’s office. During the reign of David this Abiathar continued to be high priest, but was arbitrarily deposed by Solomon, who restored Zadok, of the old high priestly line of Eleazar. The descendants of Zadok continued to hold the office as long as the monarchy lasted.

The annexed table shows the double line of high priests to the reign of Solomon:—

(1) And Hannah prayed, and said.—“Prayed,” not quite in the sense in which we generally understand prayer. Her prayer here asks for nothing; it is rather a song of thanksgiving for the past, a song which passes into expressions of sure confidence for the future. She had been an unhappy woman; her life had been, she thought, a failure; her dearest hopes had been baffled; vexed, tormented, utterly cast down, she had fled to the Rock of Israel for help, and in the eternal pity of the Divine Friend of her people she had found rest, and then joy; out of her own individual experience the Spirit of the Lord taught her to discern the general laws of the Divine economy; she had had personal experience of the gracious government of the kind, all-pitiful God; her own mercies were a pledge to her of the gracious way in which the nation itself was led by Jehovah—were a sign by which she discerned how the Eternal not only always delivered the individual sufferer who turned to Him, but would also at all times be ever ready to succour and deliver His people.

These true, beautiful thoughts the Spirit of the Lord first planted in Hannah’s heart, and then gave her lips grace and power to utter them in the sublime language of her hymn, which became one of the loved songs of the people, and as such was handed down from father to son, from generation to generation, in Israel, in the very words which first fell from the blessed mother of the child-prophet in her quiet home of “Ramah of the Watchers.”

My heart rejoiceth.—The first verse of four lines is the introduction to the Divine song. She would give utterance to her holy joy. Had she not received the blessing at last which all mothers in Israel so longed for?

Mine horn is exalted.—She does not mean by this, “I am proud,” but “I am strong”—mighty now in the gift I have received from the Lord: glorious in the consciousness “I have a God-Friend who hears me.” The image “horn” is taken from oxen and those animals whose strength lies in their horns. It is a favourite Hebrew symbol, and one that had become familiar to them from their long experience—dating from far-back patriarchal times—as a shepherd-people.

(2) Neither is there any rock.—This was a favourite simile among the inspired song-writers of Israel. The image, doubtless, is a memory of the long desert wandering. The steep precipices and the strange fantastic rocks of Sinai, standing up in the midst of the shifting desert sands, supplied an ever present picture of unchangeableness, of majesty, and of security. The term rock, as applied to God, is first found in the Song of Moses (Deuteronomy 32:4; Deuteronomy 32:15; Deuteronomy 32:18; Deuteronomy 32:30-31; Deuteronomy 32:37), where the juxtaposition of rock and salvation in 1 Samuel 2:15—he lightly esteemed the rock of his salvation—seems to indicate that Hannah was acquainted with this song or national hymn of Moses. The same phrase is frequent in the Psalms.

That the term was commonly applied to God so early as the time of Moses we may conclude from the name Zurishaddai: “My rock is the Almighty” (Numbers 1:6); and Zuriel: “My rock is God” (Numbers 3:35).—Speaker’s Commentary.

(3) A God of knowledge.—The Hebrew words are placed thus: A God of knowledge is the Lord, The Talmud quaintly comments here as follows:—Rabbi Ami says: “Knowledge is of great price, for it is placed between two Divine names; as it is written (1 Samuel 2:3), ‘A God of knowledge is the Lord,’ and therefore mercy is to be denied to him who has no knowledge; for it is written (Isaiah 27:11), ‘It is a people of no understanding, therefore He that made them will not have mercy on them.’”—Treatise Berachoth, fol. 33, Colossians 1.

And by him actions are weighed.—This is one of the fifteen places reckoned by the Masorites where in the original Hebrew text, instead of “lo” with an aleph, signifying not, “lo” with a vaw, signifying to, or by him, must be substituted. The amended reading has been followed by the English Version. The meaning is that all men’s actions are weighed by God according to their essential worth, all the motives which led to them are by Him, the All-knowing, taken into account before He weighs them.

(4) The bows of the mighty men are broken.—God reverses human conditions, bringing low the wicked, and raising up the righteous.

Von Gerlach writes of these verses that “Every power which will be something in itself is destroyed by the Lord: every weakness which despairs of itself is transformed into power.” “The bows of the heroes,” that is to say, the heroes of the bow, the symbol of human power being poetically put first instead of the bearer of the symbol. The next line contains the antithesis: while the heroes rejoicing in their strength are shattered, the tottering, powerless ones are by Him made strong for battle.

(5) They that were full.—Another image to illustrate the vicissitudes of human affairs is sketched, one very familiar to the dwellers among the cornfields and vineyards of Canaan.

The barren hath born seven.—Here the thought of the inspired singer reverts to herself, and the imagery is drawn from the story of her own life. Seven children are mentioned as the full number of the Divine blessing in children (see Ruth 4:15; Jeremiah 15:9). There is a curious Jewish legend which relates how for each boy child that was born to Hannah, two of Peninnah’s died.

(6) The Lord killeth, and maketh alive.—Death too and life come from this same omnipotent Lord: nothing in the affairs of men is the sport of blind chance. The reign of a Divine law administered by the God to whom Hannah prayed is universal, and guides with a strict unerring justice what are commonly called the ups and downs, the changes and chances, of this mortal life. The following lines of the 7th, 8th, and 9th verses enforce by varied instances the same solemn truth.

The Babylonian Talmud on these words has a curious and interesting tradition:—“Three classes appear on the day of judgment: the perfectly righteous, who are at once written and sealed for eternal life; the thoroughly bad, who are at once written and sealed for hell: as it is written (Daniel 12:2), ‘And many of them that sleep in the dust of the earth shall awake, some to everlasting life, and some to shame and everlasting contempt;’ and those in the intermediate state, who go down into hell, where they cry and howl for a time, whence they ascend again: as it is written (Zechariah 13:9), ‘And I will bring the third part through the fire, and will refine them as silver is refined, and will try them as gold is tried; they shall call on my name, and I will hear them.’ It is of them Hannah said (1 Samuel 2:6), ‘The Lord killeth, and maketh alive: he bringeth down to hell, and bringeth up.’”—Treatise Bosh Hashanah, fol. 16, Colossians 2.

(8) The pillars of the earth.—And the gracious All-Ruler does these things, for He is at once Creator and Upholder of the universe. The words of these Divine songs which treat of cosmogony are such as would be understood in the childhood of peoples. The quiet thinker, however, is tempted to ask whether after 3,000 or 4,000 years, now, with the light of modern science shining round us, we have made much real progress in our knowledge of the genesis and government of the universe.

The pillars.—Or columns—Jerome, in the Vulgate, translates this unusual word by “hinges”—cardines terrœ.

Gesenius prefers the rendering “foundations.” On the whole, the word used in the English Version, “pillars,” is the best.

(9) He will keep the feet.—This was the comforting deduction Hannah drew from the circumstances of her life: this the grave moral reflection the Spirit of the Lord bade her put down for the support and solace of all true servants of the Eternal in coming ages. Seeing that Jehovah of Israel governs the world, the righteous have nothing really to fear; it is only the wicked and rebellious who have reason to be afraid. The Babylonian Talmud has the following comment on these words:—“If any man has passed the greater part of his years without sin, he will sin no more. If a man has been able to resist the same temptation once or twice, he will sin no more; for it is said (1 Samuel 2:9), ‘He will keep the feet of his saints.’”—Treatise Yoma, fol. 38, Colossians 2.

By strength shall no man prevail.—The same thought is expressed very grandly by the prophet, “Not by might, nor by power, but by my Spirit, saith the Lord of hosts” (Zechariah 4:6). The Holy Ghost, in one of the sublime visions of St. Paul, taught the suffering apostle the same great truth, “My grace is sufficient for thee: for my strength is made perfect in weakness” (2 Corinthians 12:9).

(10) His king . . . of his anointed.—A Lapide, quoted by Wordsworth, wrote here, “haec omnia spectant ad Christum,” “all these things have regard to Christ.” Jewish expositors, too, have generally interpreted these words as a prophecy of King Messiah. The words received a partial fulfilment in the splendid reigns of David and Solomon; but the pious Jew looked on the golden halo which surrounded these great reigns as but a pale reflection of the glory which would accompany King Messiah when He should appear.

This is the first passage in the Old Testament which speaks of “His Anointed,” or “His Messiah.” The LXX. render the words “Christou autou.”

This song was soon evidently well known in Israel. The imagery, and in several passages the very words, are reproduced in the Psalms. See Excursus A and B at the end of this Book.

(11) Elkanah went to Ramah.—These simple words just sketch out what took place after Hannah left her boy in Shiloh. Elkanah went home, and the old family life, with its calm religious trustfulness, flowed on in the quiet town of “Ramah of the Watchers” as it did aforetime; the only disturbing sorrowful element was removed in answer to the mother’s prayers, and little children grew up (1 Samuel 2:21) round Hannah and Elkanah. But the life of the dedicated child Samuel was a different one; he lived under the shadow of the sanctuary, ministering with his child powers before the altar of the Invisible, and trained, we may well assume, in all the traditions and learning of Israel by the old high priest. The word “minister is the official term used to signify the duties performed by priests and Levites in connection with the service of God.

(11-36) The Service of the boy Samuel in the Sanctuary—The Dissolute Life of the Sons of Eli—The Doom of the House of Ithamar.

(12) Sons of.—The word Belial is printed here and 1 Samuel 1:16, as though Belial were the name of some pagan deity, but it simply signifies “worthlessness.” It is a common term in these records of Samuel, being used some nine or ten times. It is rarely found in the other historical books. “Sons of Belial” signifies, then, merely “sons of worthlessness,” worthless, good-for-nothing men. The Speaker’s Commentary ingeniously accounts for the use of Belial in the English Version here, and in other places in the Old Testament, by referring to the contrast drawn by St. Paul between Christ and Belial, as if Belial were the name of an idol. or the personification of evil (2 Corinthians 6:15).

They knew not the Lord.—The whole conduct of these high priestly officials showed they were utter unbelievers. They used their sacred position merely as affording an opportunity for their selfish extortions; and, as is so often the case now, as it was then, their unbelief was the source of their moral worthlessness (see 1 Samuel 2:22). “Hophni and Phinehas (the two sons of Eli) are, for students of ecclesiastical history, eminently suggestive characters. They are true exemplars of the grasping and worldly clergy of all ages.

“It was the sacrificial feasts that gave occasion for their rapacity. It was the dances and assemblies of the women in the vineyards and before the sacred feast that gave occasion for their debaucheries. They were the worst development of the lawlessness of the age, penetrating, as in the case of the wandering Levite of the Book of Judges, into the most sacred offices.

“But the coarseness of these vices does not make the moral less pointed for all times. The three-pronged fork which fishes up the seething flesh is the earliest type of grasping at pluralities and Church preferments by base means, the open profligacy at the door of the Tabernacle is the type of many a scandal brought on the Christian Church by the selfishness or sensuality of the ministers.”—Dean Stanley, On the Jewish Churchy Lecture 17, Part I.

(13) The priest’s custom.—That is to say, the custom or practice introduced under these robber-priests, who were not content with the modest share of the offerings assigned to them by the Law of Moses. (See Leviticus 7:31; Leviticus 7:35; Deuteronomy 18:3.)

(15) Before they burnt the fat.—This was a still graver offence against the ritual of the sacrifice. A contemptuous insult was here offered to the Lord. This fat was not to be eaten or taken by any one; it was God’s portion, to be burnt by the priest on the altar (Leviticus 3:16; Leviticus 7:23; Leviticus 7:25; Leviticus 7:30-31).

In all these strange rites and ceremonies there was a higher symbolism involved. This was ruthlessly set at nought and trampled on by these reckless, covetous guardians of the worship of Israel.

Portions of the sacrifice fell legally to the ministering priests in lieu of fee. It was fair “that they which ministered at the altar should live of the altar.” The “heave leg” and the “wave breast” of the slaughtered victim were theirs by right, and these the sacrificing priest was to receive after the fat portion of the sacrifice had been burnt upon the altar. But to take the flesh of the victim, and roast it before the symbolic offering had been made, was a crime which was equivalent to robbing God. It dishonoured the whole ceremony.

He will not have sodden flesh.—The meaning of this is, these priests and their attendants insisted on having the best part of the sacrificed victim raw, not boiled—that is, fresh, full of juice and strength—before the offering had been made.

(16) And if not, I will take it by force.—The solemn ritual of the sacrifice was not only transgressed by these covetous, greedy, ministering priests, but the worshippers were compelled by force to yield to these new lawless customs, probably introduced by these sons of the high priest Eli.

(17) The sin of the young men was very great.—Grave peccatum sacerdotum ob scandalurn datum laicis (“the sin of the priests was a great one, because it put a stumbling-block in the way of the people”).—A. Lapide, quoted by Wordsworth. Religion was being brought into general disrepute through the conduct of its leading ministers; was it likely that piety, justice, and purity would be honoured and loved in the land of Israel when the whole ritual of the sacrifices was openly scoffed at in the great sanctuary of the people by the chief priests of their faith?

(18) Ministered . . . being a child.—A striking contrast is intended to be drawn here between the covetous, self-seeking ministrations of the worldly priests and the quiet service of the boy devoted by his pious mother and father to the sanctuary service.

Girded with a linen ephod.—The ephod was a priestly dress, which Samuel received in very early youth, because he had, with the high priest’s formal sanction, been set apart for a life-long service before the Lord. This ephod was an official garment, and consisted of two pieces, which rested on the shoulders in front and behind, and were joined at the top, and fastened about the body with a girdle.

(19) A little coat.—The “little coat”—Hebrew, m’il—was, no doubt, closely resembling in shape the m’il, or robe worn apparently by the high priest, only the little m’il of Samuel was without the costly symbolical ornaments attached to the high priestly robe.

This strange, unusual dress was, no doubt, arranged for the boy by his protector and guardian, Eli, who looked on the child as destined for some great work in connection with the life of the chosen people. Not improbably the old man, too, well aware of the character of his own sons, hoped to train up the favoured child—whose connection with himself and the sanctuary had begun in so remarkable a manner—as his successor in the chief sacred and civil office in Israel.

(20, 21) And Eli blessed Elkanah and his wife. . . . And the Lord visited Hannah.—The blessing of Eli, a blessing which soon bore its fruit in the house of the pious couple,—his training of Samuel, and unswerving kindness to the boy (see following chapter),—his sorrow at his priestly sons’ wickedness,—his passionate love for his country, all indicate that the influence of the weak but loving high priest was ever exerted to keep the faith of the people pure, and the life of Israel white before the Lord. There were evidently two parties at Shiloh, the head-quarters of the national religion: the reckless, unbelieving section, headed by Hophni and Phinehas; and the God-fearing, law-loving partisans of the old Divine law, under the influence of the weak, but religious, Eli. These latter kept the lamp of the loved faith burning—though but dimly—among the covenant people until the days when the strong hand of Samuel took the helm of government in Israel.

(22) Now Eli was very old.—The compiler of these Books of Samuel was evidently wishful to speak as kindly as possible of Eli. He had, no doubt, deserved well of Israel in past days; and though it was clear that through his weak indulgence for his wicked sons, and his own lack of energy and foresight, he had brought discredit on the national sanctuary, and, in the end, defeat and shame on the people, yet the compiler evidently loved to dwell on the brightest side of the old high priest’s character—his piety, his generous love for Samuel, his patriotism, &c.; and here, where the shameful conduct of Hophni and Phinehas is dwelt on, an excuse is made for their father, Eli. “He was,” says the writer, “very old.”

The women that assembled.—These women were evidently in some way connected with the service of the Tabernacle; possibly they assisted in the liturgical portion of the sanctuary worship. (Compare Psalms 68:11 : “The Lord gave the word, great was the company of female singers.”) Here, as so often in the world’s story, immorality follows on unbelief.

In Psalms 78:60-64, the punishment of the guilty priests and the forsaking of the defiled sanctuary is recorded. The psalmist Asaph relates how, in His anger at the people’s sin, God greatly abhorred Israel, so that He “forsook the Tabernacle at Shiloh—even the tent that He had pitched among men. He delivered their power into captivity, and their beauty into the enemy’s hand. The fire consumed their young men, and their maidens were not given to marriage. Their priests were slain with the sword, and there were no widows to make lamentation.”

(24) Ye make the Lord’s people to transgress.—The life led by the priests publicly in the sanctuary, with their evident scornful unbelief in the divinely established holy ordinances on the one hand, and their unblushing immorality on the other, corrupted the inner religious life of the whole people.

(25) Sin against the Lord.—This touches on the mystery of sin. There are transgressions which may again and again receive pardon, but there seems to be a transgression beyond the limits of Divine forgiveness. The pitiful Redeemer, in no obscure language, told His listeners the same awful truth when He warned them of the sin against the Holy Ghost.

They hearkened not . . . because the Lord would slay them.—Here the mysteries connected with God’s foreknowledge and man’s free-will are touched upon. The Lord’s resolution to slay them was founded on the eternal foreknowledge of their persistence in wrong-doing.

There seems to be a period in the sinner’s life when the Spirit of the Eternal ceases to plead; then the man is left to himself, and he feels no longer any remorse for evil done; this is spoken of in Exodus 4:21 as “hardening the heart.” This period in the life of Hophni and Phinehas apparently had been reached when the Lord resolved to slay them.

(26) Grew on, and was in favour.—The very expressions of the biographer of Samuel were adopted by St. Luke when, in the early chapters of his Gospel, he wishes to describe in a few striking words the boyhood and youth of Him who was far greater than the child-prophet of Israel.

(27) There came a man of God.—Of this messenger of the Highest, whom, from his peculiar title, and also from the character of his communication, we must regard as one of the order of prophets, we know nothing. He appears suddenly on the scene at Shiloh, nameless and—as far as we know—homeless, delivers his message of doom, and disappears.

The term “man of God” we find applied to Moses and to different prophets some forty or more times in the Books of Judges, Samuel, and Kings. It occurs, though but rarely, in Chronicles, Ezra, and Nehemiah, and in the prophetical books only once.

Until the sudden appearance of this “man of God,” no mention of a prophet in the story of Israel had been made since the days of Deborah.

Did I plainly appear . . .—The interrogations in this Divine message do not ask a question with a view to a reply, but simply emphatically appeal to Eli’s conscience. To these questions respecting well-known facts the old man would reply with a silent “Yes.” The “house of thy father” refers to the house of Aaron, the first high priest, from whom, through Ithamar, the fourth son of Aaron, Eli was descended.

The Talmud has a beautiful note on this passage:—Rabbi Shimon ben Yochi said, “Come and see how beloved Israel is by the Holy One! Blessed be He! Wherever they are banished, there the Shekinah is with them; as it is said (1 Samuel 2:27): ‘Did I (God) plainly appear unto the house of thy fathers when they were in Egypt?’ &c. When they were banished to Babylon, the Shekinah was with them; as it is said (Isaiah 43:14): ‘For your sakes was I sent to Babylon.’ And when they will be redeemed the Shekinah will be with them; as it is said (Deuteronomy 30:3): ‘Then the Lord thy God will return with thy captivity;’ it is not said, He will cause to return (transitively), but He will return (intransitively).”—Treatise Meguillah, fol. 29, Colossians 1.

(28) Did I choose him out of all the tribes of Israel? . . .—After such glorious privileges had been conferred on this favoured house, and such ample provision for all its wants had been made for it, it was indeed a crime of the blackest ingratitude that its leading members should pour dishonour on their invisible King and Benefactor.

To wear an ephod before me.—This included the privilege, which belonged to the head of the house of Aaron, the reigning high priest, of entering the Holy of Holies—that lightless inner sanctuary where the visible presence of the Eternal was ever and anon pleased to dwell—and also the possession of the mysterious Urim and Thummim, by which enquiry could be made of the will of the invisible King of Israel.

(29) Wherefore kick ye at my sacrifice.—The imagery of the words are taken from Deuteronomy 32:15 : “Jeshurun waxed fat, and kicked . . . then he forsook God which made him, and lightly esteemed the Rock of his salvation.” The image is one drawn from the pastoral life of the people: the ox or ass over-fed, pampered, and indulged, becomes unmanageable, and refuses obedience to his kind master.

And honourest thy sons above me.—Although Eli knew well what was right, yet foolish fondness for his sons seems in part to have blinded his eyes to the enormity of their wickedness. It is also probable that he was influenced not by feelings of weak affection, but also by unwillingness to divert from his own family the rich source of wealth which proceeded from the offerings of the pilgrims from all parts of the land. These considerations induced him to maintain these bad and covetous men as his acknowledged representatives in the national sanctuary of Shiloh. Eli then allowed things, which gradually grew worse and worse, to drift, and merely interfered with a weak rebuke; but the day of reckoning was at hand.

(30) . . . but now the Lord saith, Be it far from me.—But the fulfilment of the glorious and gracious promise which involved the walking of the favoured house for ever in the light of the Lord in the blessed courts of the sanctuary with no worldly cares—were they not amply provided for without sowing and reaping?—were they not invested with high honours and universal consideration?—was necessarily dependent upon those that walked, the favoured house carrying out their share of the covenant. To be honoured of God, they for their part must be His faithful servants. Now the life and conduct of the priestly house had wrought the gravest dishonour and brought the deepest shame on the worship and sanctuary of the “King in Jeshurun.”

(31) I will cut off thine arm.—“The arm” signifies power and strength: “Thy power and strength, and that of thy house is doomed.” (See for the figure Job 22:9; Psalms 37:17.)

And there shall not be an old man in thine house.—No one more in thy house, O High Priest, who hast so signally failed in thy solemn duty, shall attain to old age; sickness or the sword shall ever early consume its members. This strange denunciation of the “man of God” is emphasised by being repeated in the next (32) verse, and in different words again in 1 Samuel 2:33.

(32) And thou shalt see an enemy.—Some—e.g., the Vulgate—understand by enemy a “rival”: thou shalt see thy rival in the Temple. The words, however, point to something which Eli would live to see with grief and horror. The reference is no doubt to the capture of the Ark by the Philistines in the battle where his sons were slain. The earthly habitation of the Eternal was there robbed of its glory and pride, for the ark of the covenant was the heart of the sanctuary.

In all the wealth which God shall give Israel.—“The affliction of God’s house from the loss of the ark remained while under the lead of Samuel there came blessing to the people.”—Erdmann.

There is another explanation which refers the fulfilment of this part of the prophecy to the period of Solomon’s reign, when Abiathar, of the house of Eli, was deposed from the High Priestly dignity to make room for Zadok, but the reference to the capture of the ark is by far more probable.

(33) To consume thine eyes and to grieve thine heart.—The Speaker’s Commentary well refers to 1 Samuel 2:36 for an explanation of these difficult words. “Those who are not cut off in the flower of their youth shall be worse off than those who are, for they shall have to beg their bread.”

And all the increase of thine house shall die.—In the Babylonian Talmud the Rabbis have related that there was once a family in Jerusalem the members of which died off regularly at eighteen years of age. Rabbi Jochanan ben Zacchai shrewdly guessed that they were descendants of Eli, regarding whom it is said (1 Samuel 2:33), “And all the increase of thine house shall die in the flower of their age; “and he accordingly advised them to devote themselves to the study of the Law, as the certain and only means of neutralising the curse. They acted upon the advice of the Rabbi; their lives were in consequence prolonged; and they thenceforth went by the name of their spiritual father.—Rosh Hashanah, fol. 18, Colossians 1.

(34) In one day they shall die both of them.—See for a literal fulfilment the recital in 1 Samuel 4:11. This foreshadowing of terrible calamity which was to befal Israel was to be a sign to Eli that all the awful predictions concerning the fate of his doomed house would be carried out to the bitter end.

(35) A faithful priest.—Who here is alluded to by this “faithful priest,” of whom such a noble life was predicted, and to whom such a glorious promise as that “he should walk before mine anointed for ever,” was made? Many of the conditions are fairly fulfilled by Samuel, to whom naturally our thoughts at once turn. He occupies a foremost place in the long Jewish story, and immediately succeeded Eli in most of his important functions as the acknowledged chief of the religious and political life in Israel. He was also eminently and consistently faithful to his master and God during his whole life. Samuel, though a Levite, was not of the sons of Aaron; yet he seems, even in Eli’s days, to have ministered as a priest before the Lord, the circumstances of his early connection with the sanctuary being exceptional. After Eli’s death, when the regular exercise of the Levitical ritual and priesthood was suspended by the separation of the ark from the tabernacle, Samuel evidently occupied a priestly position, and we find him for a long period standing as mediator between Jehovah and His people, in sacrifice, prayer, and intercession, in the performance of which high offices his duty, after the solemn anointing of Saul as king, was to walk before the anointed of the Lord (Saul), while (to use the words of Von Gerlach, quoted by Erdmann), the Aaronic priesthood fell for a long time into such disrepute that it had to beg for honour and support from him (1 Samuel 2:36), and became dependent on the new order of things instituted by Samuel. (See Excursus C at the end of this Book.)

The prediction “I will build him a sure house” is satisfied in the strong house and numerous posterity given to Samuel by God. His grandson Heman was “the king’s seer in the words of God,” and was placed by King David over the choir in the house of God. This eminent personage, Heman, had fourteen sons and three daughters (1 Chronicles 6:33; 1 Chronicles 25:4-5).

Samuel also fulfilled the prophecy “He shall walk before mine anointed for ever” in his close and intimate relation with King Saul, who we find, even after the faithful prophet’s death—although the later acts of Saul had alienated the prophet from his sovereign—summoning the spirit of Samuel as the only one who was able to counsel and strengthen him (1 Samuel 28:15).

Of the other interpretations, that of Rashi and Abarbanel, and many of the moderns, which supposes the reference to be Zadok, of the house of Eleazar, who, in the reign of Solomon, superseded Abiathar, of the house of Ithamar (the ancestor of Eli), alone fairly satisfies most of the different predictions, but we are met with this insurmountable difficulty at the outset—Can we assume that the comparatively unknown Zadok, after the lapse of so many years, was pointed out by the magnificent promises contained in the words of the “man of God” to Eli? The words of the “man of God” surely indicate a far greater one than any high priest of the time of Solomon. In the golden days of this magnificent king, the high priest, overshadowed by the splendour and power of the sovereign, was a very subordinate figure indeed in Israel; but the subject of this prophecy was one evidently destined to hold no secondary and inferior position.

Some commentators, with a singular confusion of ideas, see a reference to Christ in the “faithful priest,” forgetting that this “faithful priest” who was to arise in Eli’s place was to walk before the Lord’s Christ, or Anointed One.

On the whole, the reference to Samuel is the most satisfactory, and seems in all points—without in any way unfairly pressing the historical references—to fulfil that portion of the prediction of the “man of God” to Eli respecting the one chosen to replace him in his position of judge and guide of Israel.

Comments